It was a very big budget. Very big.

Thinking about it from the perspective of what Labour needs to achieve to secure a second term - it’s political mission rather than its mission-missions - it feels a bit like a halfway house budget to me, despite its size, because:

Reeves is gambling on growth but opted for the lesser of two options for increasing borrowing headroom (i.e. PSNFL instead of PSNW).

She’s prioritising public services, but despite the huge tax hike, still may lack the fiscal space to make a real, felt difference.

There weren’t any household giveaways and the sum total of their measures are, according to the IFS, going to slow the previously forecast (see the IFS chart, the first in the linked piece) growth in household disposable income.

There’s almost no point in saying this now, but the underlying issue is that prior to being elected, Labour boxed itself into several positions it has since been trying to unbox itself from. Changing the debt rule is one bit of unboxing, but another might have been using exceptional circumstances (ailing economy, climate urgency, public services on their knees) to run a deficit budget. On this it is still boxed in

In addition, having committed to a balanced budget (i.e. no deficit), being left with a growing fiscal deficit leaves you only one choice, and of course Truss’s 2022 mini budget still looms large over the UK fiscal landscape.

Green Budget?

For those of us working on green and climate, it’s important to note that the budget took place against the backdrop of the absolutely catastrophic floods in Spain. The UK’s budget-obsessed media has scarcely mentioned this let alone joined any of the dots to the paucity of our public realm and lack of preparedness. Nevertheless, there are some reasons to be cheerful - more than, perhaps - when looking at the post-budget fiscal picture.

DESNZ did well, with a big uptick in investment gifted from the new fiscal rules, which shows the clean power; lower energy bills agenda is very live inside the government. It’s a gamble, but one we should wholly back.

Public investment is key to green industrial strategy and the decision to go early on the fiscal rules change, when many thought it would be left until later in the Parliament, is a good one, even though many of us would have favoured the ‘net worth’ measure of public debt.

Allocations to GB Energy, the new state owned energy investor, and the National Wealth Fund, the new policy bank, have gone through as expected and Industrial Strategy was foregrounded as a mechanism for getting growth. All of the key policy areas on which Labour came into power are still not only in play but at the top of its agenda in government.

The big picture, for all its downsides in terms of tax incidence, is the government understands that its mission (both in terms of issues and more broadly its political mission) is heavily reliant on investment and on a rejection of austerity (Resolution Foundation says an annual average real terms increase over the next 5 years of 2%, which it also says is probably not enough).

On this last point, the spending review in the spring, at which longer term departmental allocations will be decided, will probably show that health and education are the first among equals and so it doesn’t mean that some departments (e.g. probably the environment ministry - Defra) will avoid cuts in absolute let alone real terms.

More Panglossianism is available from Sam Alvis over on the Election Energy Substack. I’m not sure I’m as enthusiastic about £20bn for CCUS, but his general point is a very good one.

Households and Growth Are Key

Looking at the government spending watchdog (Office for Budget Responsibility) projections, the effect of the budget is to push forecast growth up significantly in the first year, but then down to below previous forecasts. As IPPR and the FT have pointed out, this is almost certainly a quirk of OBR models in that they only apply multipliers once. Again, see the Resolution Foundation’s paper.

A bigger political, though not explicitly green, worry, would be that OBR forecasts for the impact on household disposable income - in my view (a bit old, but still stands) the most critical measure of how well the nation is doing - are that it will grow more slowly than previously thought. This too is a bit linked to the way they forecast growth.

Of course, the biggest single thing Reeves did was the hike in the national insurance contributions of medium and large businesses; worth a forecast £25bn. OBR’s assumption is that this will, at least in part (I don’t know how much of a part) be passed through to workers in lower-than-otherwise wages (or to consumers in higher-than-otherwise prices). I would add though on this that in markets where competition is significant, both for customers and workers, it would then act, at least in part, as a profits tax.

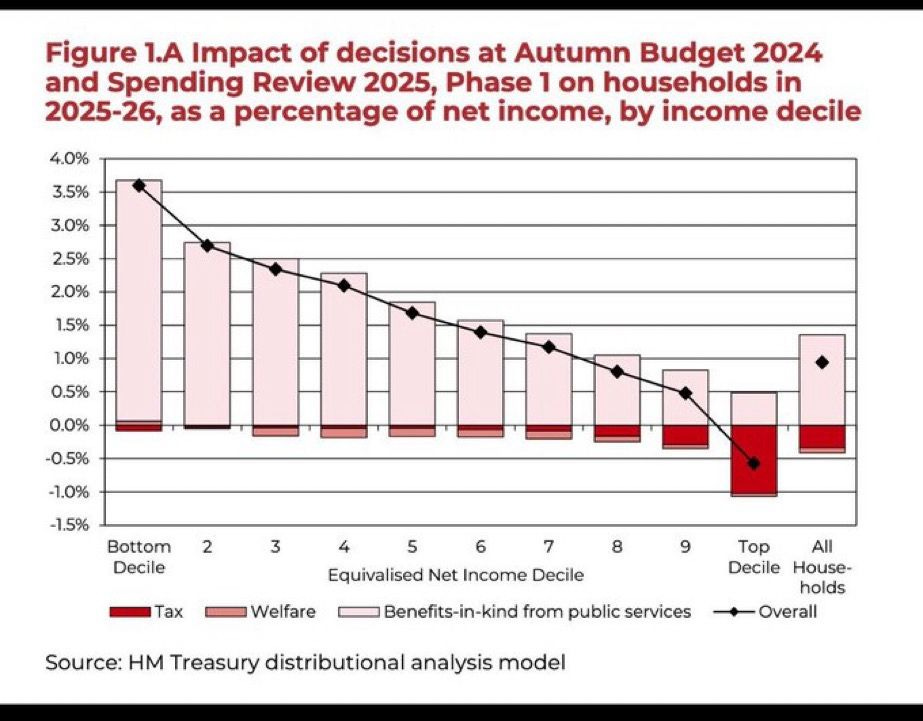

The way tax-benefit changes distribute across UK households by income deciles is always an important way to look at any budget. It may be that in aggregate household income is not forecast to rise very much, but if this from the HMT impact assessment is right, then those who might benefit most are households with the lowest incomes.

This goes back to the top. If you half try and solve something, there’s a chance the other half will come back to bite you. Only time will tell (he says, copping out of a firm commitment), whether somewhat more public investment and somewhat more daily spend on services will be enough.

Let’s hope the extra investment, the multipliers, the benefits to low income households, the cash put into services and some fair global economic winds combine to make this half full rather than half empty.