Someone else's growth

People's experience of the economy may well have created some of the conditions for Trump's victory. Many of the same factors exist in the UK.

I started writing this piece a month ago. Honestly. Following today’s pivot-not-pivot from the UK government, it feels a bit like wasted effort.

It would be naive to suggest that the wave of far-right nationalism that’s breaking across the developed world is all about the economy. There are lots of social and cultural aspects of the Republicans’ win in the US, for instance, that I don’t understand. And, from US friends, a very large dose of Democrats messing up.

But if, as many have argued, it was at least in part about the economy then what stands out is the decoupling of GDP or GVA growth and living standards, especially since the financial crisis. This suggests that, while important, getting more from less in the economy is not in itself enough to deliver the UK from the same sorts of forces. The Prime Minister is right to focus in on livings standards.

But, more than this, it’s about the interaction between falling livings standards and the liberal political economy and the ultimate failure of trickle down.

1. Static or falling wages and household disposable income

This useful country case study from at Institute for Fiscal Studies highlights how average incomes among men in the US with lower levels of education have remained static or declined over the past 40 years. Overall, income inequality has increased significantly during this period, with wage inequality among men experiencing a 40% Gini coefficient increase, which is particularly stark.

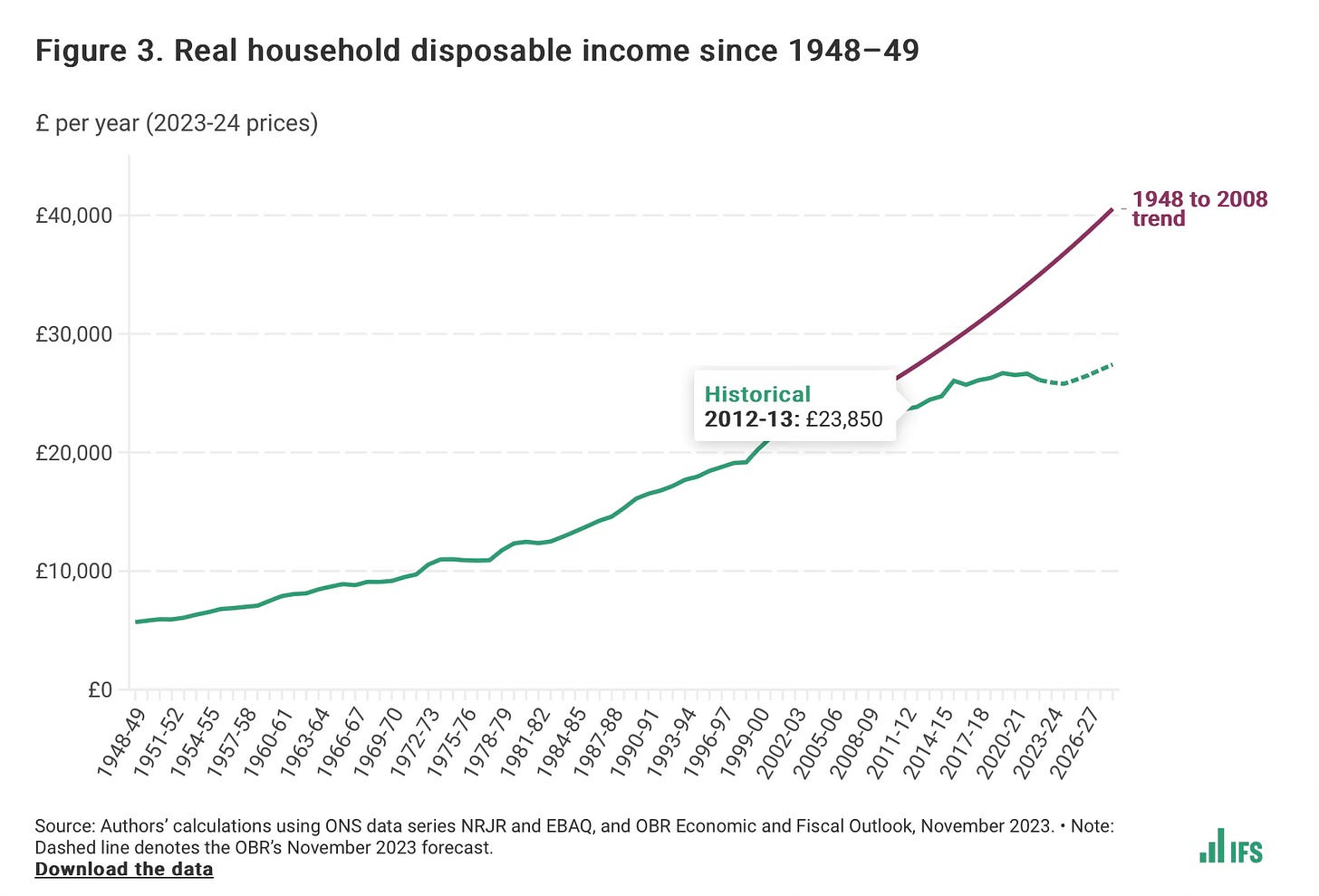

In the UK the story isn’t entirely the same, but the turning point is the 2008 financial crisis, when improvements in disposable income departed from trend, as this well known IFS graph shows:

The graph was produced in January 2024, before Reeves’ budget, which has unfortunately shifted the assumption of future growth in real incomes (the dashed green line) downwards.

This matters because, unlike GDP growth, it’s an indicator of how well off households are feeling. Because it’s an average, and because household incomes in the UK are hugely unequal, what it also implies is that many - perhaps most - UK households have experienced more than a decade of declining livings standards. The recent cost-of-living crisis will only have intensified an already chronic problem,

When I looked at levelling up for NEF in the aftermath of the 2019 UK election, I concluded that the most important indicator was household disposable income after housing costs. This was because in almost every part of the UK, outside of a few postcodes in core cities and the south east of England, people do not have a lot to live on, once they’ve paid to keep a roof over their heads.

A clear indicator of this, as this paper from John Van Reenan (now a Reeves adviser) suggests, is the growing gap between average and median wages. Higher pay at the top drags up the average, but the median point does not grow at the same rate due to a rump of stagnating wage growth across the economy.

In effect, what this means is that for most people, GDP, GVA or productivity growth, however anaemic in itself, has not translated into better living standards and, especially since the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis, many are worse off.

For those with lower incomes, cuts in public spending act as a double whammy as collective assets like childcare, public transport and and social care, as well as the wider benefits system, are diminished, leading to a reduced social wage.

2. That’s your growth, not mine.

The growing inequality, decoupling of wages from productivity growth and chronically low or falling real terms disposable incomes is not just an economic phenomenon. It is acutely political.

There probably isn’t a straight, causal line between people’s stagnant pay and the rise of populist politics (Aditya Chakrabortty argues that blaming ‘populism’ is lazy thinking), other factors are at play - increasingly a polluted online information ecosystem is driving discontent.

But within the aegis of the political economy, the problem of stagnant average living standards, coupled with failing public services, along with high levels of inequality and a very distant polity (government in the UK is especially centralised) is a potent mix.

In many respects, this is the ‘winners and losers’ narrative of the Washington Consensus coming back to bite liberals. The gap in industrialised countries between those who’ve benefitted from the period of ‘hyper globalisation’, as Dani Rodrik calls it, isn’t just measured in income or wealth inequality, but also in political dissafection. Ben Ansell’s excellent paper for the IFS’s Deaton review articulates this link perfectly.

The lives of those whom the populists call ‘elites’, who work in high-level politics and institutions, finance, footloose services (and even to a certain extent in non-governmental organisations), and most people’s daily experience are highly disconnected. All sorts of other phenomena, such as educational outcomes and the point from which each of us starts out all impact on individual households in one way or another, but people’s feeling of being worse off and more disconnected is a potentially powerful recruiting sergeant for populism.

A focus on improving livings standards

The famous quote alluded to in the title of this post comes from a story told by Anand Menon of King’s College London (retold here in the Guardian). Speaking to an audience in Newcastle about the risk of Brexit to growth, a woman in the audience yelled back ‘that’s your bloody GDP, not ours.’ And therein lies the problem with a focus on GDP alone in a highly unequal economy which is largely now prefigured to concentrate wealth at the high level and among capital owners.

No-one would envy the fiscal position in which the new government finds itself. The deficit bit, closed clumsily with the employers’ NI increase, is particularly problematic because, despite the very important calls for more taxation of wealth, It’s hard to see how improving GDP growth to fill the gap in the exchequer is unimportant. We can all be opposed to austerity, but unless the Chancellor can increase revenue, over the longer term, there’s only one other option.

However, the focus on GDP needs to be accompanied by measures to reduce inequality which include revenue raising through wealth taxation, and more ownership by people of firms and assets and, probably in the short term, by giving cash to help households through inflationary spikes. End the two child limit of Universal Credit now! Surely.

On its own, the push to raise GDP, even if successful, could still leave a large number of UK households feeling worse off, especially in as short an economic space of time as this Parliament.

As soon as this winter, with the energy price cap already increased, all it would take is for some additional food price inflation - perhaps caused by all the extreme weather in Europe - and colder temperatures than in recent years. Many households - and the government - would be in a lot of trouble.

It’s only a shame that Starmer and team didn’t approach it like this from the start. It’s been very obvious for more than a decade that stagnating living standards was a powerful vector for the wrong sort of politics and a decay in political trust. A more resilient, prosperous (and of course green) economy is going to be essential. All of the focus on industrial strategy and investment must not be lost. But growth needs to be for everyone and not just for someone else